Metadata standards

The article below contains general information useful for choosing standard for describing objects stored in the digital library. A reader can also find information about standards used in other similar branches - museums or archives.Which metadata schema will be good for me?

Let’s start the real work! According to the check list, identification of requirements and best practices used in similar existing collections should be done in the beginning. While describing this stage we will refer to 9 questions formulated by Marie R. Kennedy. The mentioned 9 questions help to identify requirements, and thanks to this collection developers are able to consciously decide which metadata tools and standards might be the most useful for a newly created collection. Not all questions are relevant at this stage, so they will be omitted, and for the full list of all 9 questions study the full paper [source].Who will be using the collection?

Will it be an ordinary Internet user or an expert historian? This determines several things: language used in descriptions, a question if it is useful to use controlled vocabularies and how detailed descriptive metadata should be. Sometimes it is hard to determine who will be the user of the collection, and in such a case you should assure as many entry points as possible, i.e. use the present names of streets as well as historic once.Who is the collection cataloguer?

Does the cataloguer have domain knowledge or not? Are they able to fill in the complex metadata schema? You have to remember that one metadata record can be divided and developed by a few people at once. Some of them have domain knowledge, others know details of metadata schema and can help to fill in the given metadata properly.

How much time/money do you have?

It is obvious that the richer the object description is, the bigger chance there is that users will use the collection. From what was already said it seems that in order to prepare rich metadata it is necessary to have:- an accurate metadata schema,

- cataloguers proficient in using this schema

- and most likely some domain experts might be helpful.

How will your collection be accessed?

The most important issue here are the capabilities of the digital library system which will be used to assure access to your digital resources. Does it support complex metadata schemas? What searching capabilities does it have? If users are not able to use the whole richness of our description, the question is whether it is worth creating such rich metadata.How is your collection related to other collections?

This is important mainly because of interoperability issues. If you have identified a similar collection, it is very likely that you might be interested in creating a reference to a resource from that collection. Thanks to showing related resources in an object’s description, users will have a chance to acquire additional information.It is also very likely that at some point both collections will be searched through the same searching interface thanks to harvesting (see the next paragraph). In such a case it is worth assuring common understanding of some terms and common encoding rules, e.g. for dates.

If your library has an OPAC, it is also a common practice to link between an OPAC record of a physical object and digital reproduction in a digital library.

What is the scope of your collection?

By determining the scope you would be able to cut off some non-related metadata standards. Is there any dedicated metadata standard for your type of resources? Are there any controlled vocabularies dedicated to your objects?

If a collection with a similar scope exists, it is worth taking a look at solutions which were employed by its developers. This opens a possibility to save some time and money by choosing similar metadata tools (schema, controlled vocabularies). But since every digitisation project is different, you should still evaluate their findings on your own to avoid their mistakes.

Will your metadata be harvested?

Harvesting is an act of collecting web resources by a dedicated computer program. Such a computer program (sometimes called web-spider) is usually used by web searchers to get information necessary for creating their index. In the domain of digital libraries special harvesting protocols were developed — Open Archive Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH) is the most widely used. If your collection is harvested, which is a case for most of the currently developed collections, you should be aware of requirements of this protocol. OAI-PMH is generally compatible with all XML-based metadata schemas, but it features a basic requirement: collection’s metadata must be available at least in DCMES. Your collection may be described using virtually any number of an XML-based metadata standard but in order to be an OAI-PMH compliant repository it has to expose metadata in Dublin Core.

If DCMES seems too simple for your collection and you will choose a more suitable standard, you will have to remember to provide an appropriate mappings and conversion mechanism to enable OAI-PMH harvesting of DCMES.

Enough questions, it is time for some answers! On top of knowledge gained in the previous lesson and answers to questions described you should identify a group of potential metadata tools suitable for your collection. Sometimes it is hard to decide whether it will be the lack of appropriate standard, experience or knowledge. In such a case you should consider using Dublin Core Metadata Element Set or Dublin Core Terms. And if everything fails, the existing metadata standards are not useful for describing your collection and you can always create your own application profile.

Application profiles

Various metadata standards defines mechanisms which allows for schema extensions. Most often schemas are extended through, a so called application profiles (AP). It is defined as schemas which consist of data elements drawn from one or more namespaces, combined together, and optimised for a particular local application - [source].

Creation ofng an application profile is usually associated with mixing various metadata standards in order to provide better resource discovery within a given domain. Applying application profile requires keeping in mind that you will have to maintain appropriate mapping in order to achieve sufficient level of interoperability [source].

When changing metadata schema it is always better to qualify an existing element rather than create a new additional element. Thanks to this it is always possible to collapse richer representation into the original schema when it will beis required to comply towith the original schema.

When adding new elements to a given schema, it is preferable to draw on other metadata standards if possible.

In case of any additions, refinements or other extensions (e.g. changing an optional field into mandatory elements) isare necessary to document these changes publicly. This would allow interested parties (including users of your collection) to understand the applied approach and use digital resources from the collection more efficiently.

More interesting suggestions about metadata schemas extension can be found in [source]

The following sections contains short descriptions of the selected metadata standards from different domains including libraries, museums and archives.

Categories for the Description of Works of Arts (CDWA)

CDWA [source] was created as a means to describe cultural objects like museum exhibits. This specification was a result of work started in the 1990s by “The Art Information Task Force (AITF), which encouraged dialogue between art historians, art information professionals, and information providers so that together they could develop guidelines for describing works of art, architecture, groups of objects, and visual and textual surrogates”. It is build out of 512 categories (which may have sub categories); as you see, it allows to create a very detailed description. CDWA identifies a set of 35 core tags which should be used as a minimum. Comparing this to DCMES seems to be a very complicated standard. In 2005-6 a CDWA Lite developed this specification to allow for XML serialization of metadata records created using CDWA.Main categories of CDWA include the following: Object work type, Title, Display creator, Indexing creator, Display measurement, Indexing measurement, Display material/technique, Indexing material/technique, Display State/Edition, Style, Culture, Display Creation Date, Indexing Dates, Location/Repository, Subject, Classifications, Description, Inscriptions, Related works, Rights to work, Record, Resource.

Unlike DCMES, CDWA includes both information about the original version and digital surrogate. All elements are repeatable. It is also worth mentioning that CDWA Lite conforms to OAI-PMH, so as well as ordinary DCMES it enables digital collections to work together.

Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS)

MODS [source] is a directly derived from MARC 21 and it was designed to simplify MARC descriptions. It is buildt out of the subset of MARC 21 fields and it uses natural-language based labels for field rather than field numbers as they are used in MARC. MODS is encoded in XML, so all metadata records compliant with MODS are also compliant with XML as you already know this results in smooth processing by computer programs.Note: What does it mean that XML is eXtensible? Let’s consider an example file compliant with the Open Document Format (an ISO standard for text-based documents, encoded in XML) it can be simply extended with Dublin Core features like Creator or Publisher elements (in XML world such an extension is called namespace) and it still would be a valid Open Document Format file. It will also be a valid Dublin Core document. In case of most XML-based standards it is very simple to combine them together in one structure. As each of them is formally described, computer programs does not have any problems with its interpretation. That’ is why XML is called eXtensible.

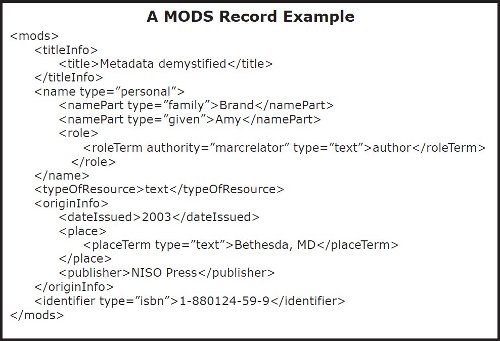

MODS is particularly interested in enabling a rich description of digital resources. Thanks to Dublin Core Metadata Terms such a rich description can be also be created using DC Terms, but in case of MODS this feature was present from its beginnings. According to the “Understanding Metadata” [source] brochure, MODS is more compatible with library data than Dublin Core -, which is understandable considering its tight relationship with MARC 21. Although compatible, MODS offers some enhancements over traditional MARC 21, including: an optional ID element to facilitate linking at the element level, the ability to specify language, script and transliteration scheme at any level. Figure 1 presents an example of metadata record created using MODS [source].

Figure 1: Example metadata record encoded using MODS [source].

Lightweight Information Describing Objects (LIDO)

LIDO as a part of work developed under the Athena European Commission funded project aimed at delivering museum objects from all over Europe to Europeana (European museum, archive and library). The introduction to LIDO specification motivates creation of yet another metadata standard in the following way: “There is a common view within the museum community that a DC derived metadata schemas do not deliver a rich enough view of museum content. The importance of a museum object, especially outside the area of fine art, is often not covered adequately” . Museum metadata formats (i.e. CDWA, SPEKTRUM) introduces a very rich description of objects which creators of LIDO spec find hard to compare with the “flat” structure of Dublin Core. Apart from this, creators point out the following deficiencies of DC:

no tools to create relations between different classes and events they relate to,its extensibility (DC allows for extension) is a barrier to interoperability

LIDO was created on top of existing museum schemas, in particular with an ISO standard called CIDOC CRM. LIDO is also compliant with CDWA Lite and museumdat standards. Thanks to the fact that LIDO extends renowned standards it has a chance to become widely applicable.

It has to be mentioned that LIDO is a harvesting schema and it should not be used as a basis for collection management. It was created mainly to deliver rich metadata for organisation’s online collections database and portals.

LIDO record is divided into 7 areas :

- Object Identification — basic information about the object

- Object classification — information about the type of object

- Relation — relations of the object to its subject and to other objects

- Event — events that the object has taken part in, including: Creation, Acquisition, exhibition, etc.

- Rights Work — information about the rights associated with the object, metadata and the digital surrogate being harvested into the service environment.

- Record — basic information about the record

- Resource — basic information about the digital resource being supplied to the service environment (e.g. Europeana).

General International Standard Archival Description (ISAD ) and Encoded Archival Description (EAD)

ISAD [source] defines general rules for archival description that may be applied irrespective of the form or medium of the archival material. It consists of twenty six elements that may be combined to create the complete description of an archival entity.EAD [source] is a standardised XML schema which was developed to mark up a data from archival finding aids. Finding aids are something a bit different than usual metadata record (from the librarian point of view) they are much longer, more narrative but also highly structured. Finding aid starts with a description of the collection as a whole, explaining what kind of materials it holds and why they are relevant. It is really hard to imagine a whole biography of an author as a part of metadata record but it fits perfectly into a finding aid. In the end of such an elaborate document a user will find information about how the given content is physically stored, i.e. the number of boxes. EAD is particularly popular in academic libraries, historical societies, archives and museums. Such institutions possess a large special collection which in most cases does not own unique records for each item.

Metadata encoding and transmission standard (METS)

METS [source] is not a descriptive metadata standard; as its name stands, it was designed rather to provide a standard data structure for complex digital library objects. METS is an XML-based schema, it allows to create one document holding information about:- object structure, e.g. list of pages in a book in an appropriate order

- associated descriptive, (e.g. a DCMES or MODS metadata record) and administration, (e.g. information about digitisation process) metadata

- links to files representing the content of the object, it is also possible to embed content inside a METS record.

- METS Header — basic information about METS document, e.g. creator,

- Descriptive Metadata – this section contains descriptive metadata but it can also present links to external metadata records,

- Administrative Metadata – technical information about how files were created, stored and other information (also Rights information),

- File section – list of all files which are a part of this object,

- Structural Map – models a structure of the objects, links files with appropriate metadata records,

- Structural Links – “allows METS creators to record the nodes in the hierarchy outlined in the Structural Map”,

- Behaviour – associates executable behaviour with the content stored in METS file.

References

- "Nine questions to guide you in choosing a metadata schema", Marie R. Kennedy, [source]

- "Metadata standards and interoperiability", JISC Digital Media, [source]

- Format Categories for the Description of Works of Arts (CDWA), [source]

- "Metadata Object Description Schema, [source]

- Internal Standard Archival Description, [source]

- Encoded Archival Description, [source]